This episode is produced as part of our RAP commitment to communicating our learnings and sharing case studies from implementing our RAP.

Stay in touch with us on Instagram.

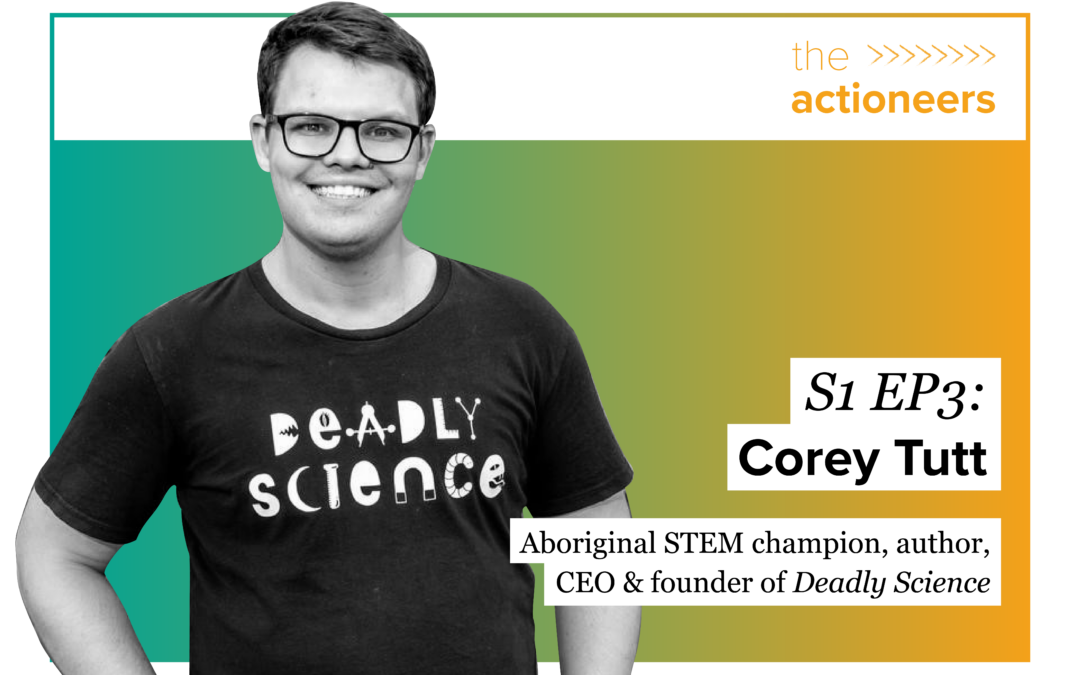

About Corey Tutt

Corey Tutt is a proud Kamilaroi man and Young Australian of the Year for NSW 2020.

He is the CEO and founder of the charity DeadlyScience, which provides science resources, mentoring and training to over 110 remote and regional schools across Australia with a particular focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Current Work:

When Corey learned that there was a remote school with only 15 books in the whole library (5 of which were dictionaries) he set out to make change. To date, DeadlyScience has provided over 15,000 culturally appropriate books focused on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) as well as telescopes, microscopes and other equipment to spark student interest. Schools involved with DeadlyScience have reported a 25% increase in engagement in STEM and increased attendance.

As a board member of Science Technology Australia, Corey is contributing to the development of their first Reconciliation Action Plan to further encourage participation and inclusion of First Nations peoples in STEM.

Corey’s passion for Indigenous education has also been recognised through various awards including the CSIRO Indigenous STEM Champion 2019; AMP Tomorrow Maker 2019 and ABC Trailblazer 2019, 2021 Eureka prize finalist winner.

Transcript

[00:04:09] Melanie: Alrighty. So, today we’re welcoming Corey Tutt. He’s a proud Kamilaroi man. He’s also the 2020 New South Wales, Young Australian of the Year. He’s the founder of Deadly Science, which is an initiative that provides science books and early reading material to remote schools in Australia. Deadly Science recently was awarded the department of industry science, energy and resources, Eureka prize for stem inclusion. Welcome

[00:04:38] Corey: Yama and thank you for that.

[00:04:40] Melanie: Oh, you’re so absolutely welcome. We were delighted to learn about the First Scientist, but, first we learned about Deadly Science because obviously your organization and ours, working in a very similar space.

But before we get into all of that, I’d love to learn. More about you and how it is that you came to establish your own charity and then, you know, go on and write a book. So what’s your story, Cory?

[00:05:09] Corey: Well, actually it starts, it starts probably from when I was around two years old. My father, unfortunately left my mother at two. And, it meant that I grew up with my older sister and, and my mom, often we, couch surfed and moved around a lot. And, it was really hard. For me as a, as a baby, because, my grandmother’s mom refused to hold me because she thought, I was named after an Aboriginal man and, and I was Aboriginal.

So my mum didn’t get a lot of support and my nan died when she was 42. But I had always had a love of nature and because we’re moving around a lot, I absolutely loved, you know, Catching lizards in the backyard. That was my favorite thing to do. And we all know like a little kid that does that.

For me moving around a lot, whilst I was going to school in belie, and this is an important point and part of my story, You know, I witnessed a fatal accident that, tragically led to the death of my classmate. That was, that was hit and killed, And I think that that is the moment where I became a very empathetic person and, you know, I always, you know, if I ever got in trouble on the playground or something, I always felt guilty and always, it was very sad and I was always empathetic. So I think moments like that make you, make you really strong and name they, they make you either do one or two things. I guess probably to regress a bit in your behavior, which I probably did that a little bit. But also they, they make you appreciate life because you realize how, how finite and how, how life can be taken away from you. Very, very quickly.

I remember my pop gave me a book not long after that, which was Reptiles in Colour, Harold Cogger and that’s the book that taught me how to read. You know, I learned how to read and my first ever science experiment was chasing water dragons into a dam and getting a stopwatch and, and timing how long they can hold their breath under water. And it was about an hour. So, you know, those things are the things that bring you joy in life. And they brought me joy.

You know, I sat across my careers advisor at 16 and I, he said, what do you want to be when you leave school? And that’s a pretty good question. And I said that, I wanted to be a zoo keeper or wildlife documentary. Cause I was reared on Harry Butler, I wanted to be the first black fellow version but, you know, I was told by my career’s advisor, that kids like you, cause I went to a school in Dapto (Wollongong NSW). Kids, like you don’t really go to university or, or do those kinds of things. It’s going to be really hard for you. You should probably stick to a a trade, or you end up in jail or worse. And that was said to me to, to probably spur me on, to be, you know, to go. Probably get a trade and, but I was a very determined kid, even when I was young. I remember I got told that I was too small for a football team, so I literally tackled every player on that team. Just so I could make the team and. You know, I, I wouldn’t take no for an answer. If someone said I couldn’t do anything, I would take it really personally. And I would prove them wrong and not much has changed.

I’ll always had a respect for the strong women in my life because I had a really strong sister and I had a strong mom and, they didn’t have the best, my sister and I didn’t have the best upbringing, but we, we may do what we had.

I left school at 16 and I went to a place called Boyup Broke in Western Australia. And I worked at this now, defunct wildlife sanctuary,Roo Gully. And, and I don’t want to be rude, but, it was kind of like disorganized chaos. And I liedabout my age. I said I was 17. I said I was doing animal studies and I’d signed up for animal studies and I did it on the plane on the way there didn’t do any of the modules. I’d literally just did it, all the assignments on the plane over there and rush them. And I ended up passing some miracle I passed, but when I went over to West Australia for the first time I stayed with this couple called Jim and Norma and Jim and Norma are nolonger with us, unfortunately, but they were the first people that showed me any kind of love as a child.

And then basically what happened was I came back to. New south Wales, just after my 17th birthday. And I started working at this place called narrow wildlife park, which is now known as Shoalhaven Zoo. And, it was an interesting place. I was keen as mustard and the first day I went there they told me to get there at 8am and I got there at 7am and I was just sitting inside. I was waiting for my chance to, you know, to achieve this dream that I’d had of being a zookeeper. And, the zookeeper said to me, he’s like, why are you so keen?

You know, you’re going to be scrubbing toilets all morning. And I’m like, I didn’t care. I was just happy to be there and he would say, oh, you know, you’re not capable of doing this. But I would always just always outdo him and prove him wrong. And if he said I couldn’t rake fast, I’d be there the next day, raking twice as fast and I’ll be doing it even better. I worked my butt off to, to prove it wrong.

Then I’d become friends with a guy down there that we became really good friends. Cause we, you know, he volunteered there and we really liked reptiles and he’d left the zoo, but we’d stayed in contact and we were deciding that we’re going to live together. And then unfortunately he, he, he made a really bad decision one night before we were meant to move in together and he, had hung himself. And committed suicide and, that whole love of animals made me unique and cool. And, when you lose that enjoyment for things, it’s a pretty scary time because, you know, I’m very passionate about animals and nature. And, for me, I’d lost that completely. And it was like, I reckon it would have been easy to lose a limb, to be honest. Because at least when you lose a limb, you understand what you’ve lost. And for me, I, it took me a really long time to work out that I was a broken person, you know, And I saw, I was sort of, I wasn’t having fun at the zoo anymore.

And I ended up. I ended up seeing an ad in the Illawarra Mercure for an alpaca handler , and I feel a bit stupid now because I wore my year 10 formal suit, which was a classic suit that I got from Lowe’s. And you know, I was a bit of a Good Charlotte fan back then. So I, to give you an idea of what it looked like, I had, you know, a white top hat, a black shirt, white suspenders and white tie and white belt, black pants and white volleys.

And it was a bit of a look at the time, but it was extraordinary. It was back when good Charlotte were popular. I’m

[00:11:10] Melanie: sorry. More people should wear an outfit. Like.

[00:11:12] Corey: Oh, yeah, for sure. So I wore this to my alpaca interview. I thought I’d get the job. I thought it looked really good and I feel a bit stupid now because I ended up, becoming, I ended, he ended up saying to me straight away, like start Monday and he’s, and then eventually later on I’m like how many people actually applied for that?

And he goes, you were the only one. And I’m like, I literally went to this guy’s house, wearing a suit, to apply for a job that no one else had applied for that. Obviously going to get,

[00:11:37] Melanie: I’ll bet he still tells that story till today. That’ll be one, that’ll be a Friday night drinks one.

[00:11:43] Corey: Yeah. There’s a really good podcast of James Dickson and I, and it’s called walking together and it’s, it’s about, you know, me being an indigenous person, him being a non-indigenous person and how we had this journey together.

And, Yeah, I’m not going to sugar coat James sidebar life, because I was, I was probably really depressed at that stage. And I was looking for someone to open up to, and I didn’t really have anyone that I could open up to. You know, it wasn’t like. I had my best friend here. That was, he wasn’t alive, you know, he was dead.

And I didn’t really have anyone. I didn’t really have anyone I could confide in. It wasn’t like it was something that was advertised. It was, it was really hard and, and suddenly those, those things that happened when I was a child, they started to come back, you know, and things that I suppressed phages and I guess.

Yeah, the moment I realized I was a resilient person, was the moment where the first, alpaca we shaw together I think it was called Pikachu at the time, and might have a different name now, but it head-butted me in the face and cracked my cheek bone. And I remember James asking me if I was alright I something in me just kept me going and it just like, it kept me going. And I knew that I couldn’t quit on this job because if I quit it on, if I quit on this job, I w would have been quitting on life. And, I kept going and we went around Australia and New Zealand together and we sheared Alpacas. And it made me, you know, it made me strong as a man. It made me, you know, able to be, to be able to give my opinions in a respectful way. You know, and I think James was very much like a father I never had.

But you know, it was, I was always driving myself for the next big thing, because I was never content with just being, you know, just being in an Alpaca shearer I never wanted to do that. I just, you know, for me, and even being a zookeeper wasn’t enough, you know, it was never enough. And, and maybe that’s just the drive in me to, to overcome. You know, the adversity that I’ve overcome, but also that I never really wanted people to tell me what I couldn’t couldn’t do.

And I wanted to be the maker of my own existence, so to speak. Did

[00:13:41] Melanie: you have, did you have a, at that stage, a bigger picture idea of where you were heading or was it a crooked path, quite opportunistic that led you from one point to another?

[00:13:53] Corey: It was opportunistic. I I’d had a friend, you know, from zookeeper and get a job at the RSPCA and, I really needed a job at that point because I decided that I wasn’t going to have another year of shearing because it served its purpose for me. I mean, there’s only so many alpacas or lamas you can shear, once you’ve sha you know, once you’ve shown, you know, a few thousand of them, then it’s, it’s kind of served its purpose and,

[00:14:16] Melanie: and ask what’s a ballpark figure on the, how many alpacas you’ve shared.

[00:14:21] Corey: Oh, we used to do 10,000 a season. So I’d say it’s probably between 30 or 40,000.

And, I didn’t anticipate it, but I saw the very best and worst in humanity at that point, when I worked at the RSP CA because I had seen, you know, dogs and cats get rehomed to the most loving people. But then I was at the same time, I was seeing humans, humans, treat animals, just so abhorently, and then that was the things that, those are the things around that, that like, you know, you couldn’t really get your head around it. Like you couldn’t get your head around, like how someone could, could go and purchase a dog off a breeder or a pet shop. And then, six months later, they’re shoving it in a cage out of the front of the RSP CA with no food, no water, and treating their animals so badly. When they bring us so much joy, like I used to love that job in the sense of, I used to go into the paddocks and kick the soccer ball around with the dogs and, I really loved it. And Bouncer was a unique story. Had his throat cut by, this nasty individual but he was just dumped in a bin and literally, required hours and hours and hours of surgery to just to survive. He was really beautiful. I, he gave me a lot of hope for humanity in the sense of life and, and life because, here’s this dog that’s going through so much adversity, yeah, it doesn’t hold grudges.

And I actually learnt a lot from that dog. In the sense of like, if a dog can not hold grudges towards humans for what humans have done to it, then what is my excuse for holding grudges?

[00:15:53] Melanie: You know, sometimes I think our pets are our greatest

teachers.

[00:15:56] Corey: Definitely, definitely they very much so. I ended up meeting my, my partner and my fiancé at that animal shelter. And I’ve never looked back since.

I ended up studying animal technology and I went to, the Garvin (The Garvan Institute of Medical Research) at first and I worked with Garvan as animal technician. And I ended up getting a job at the University of Sydney and, that’s how the Deadly Science stuff started I figured that, you know, whilst I’m still young, I can go and speak to some of these kids and maybe, you know, if they’re going through similar things and they want to potentially find a career in science. And, and then we started the science talks and they just went off.

They became really popular, like extremely

[00:16:33] Melanie: Were they face-to-face. So this is definitely yup. Yeah. And groups that are settings? So like a, a large audience, or

[00:16:41] Corey: It was a large audience. It was, between, you know, like there was 20 or 30 kids and this was previously with the AIM Program, but then the AIM Program stopped doing the face-to-face stuff. And I continued to do these talks and these kids would come from Alex Park. They’ll come from Redfern, they’ll come from Waterloo and would just talk about stuff. You know, how does a blue tongue have a blue tongue? Like how do we get food to the space station? You know? So far I didn’t even know about. So I started like learning and reading textbooks and things like that. Just to have new things to talk about on a Friday afternoon.

And, they went really well. And then I had, had one of the kids, talk to me. I think he might’ve been a Monroe boy and he said to me, why is it that, why is it that you’re investing so much time in us and talking about science when none of our teachers are. You’re the only one that’s saying we can do science.

And I wish I got given like animal books when I was a kid, because I really want to be a zookeeper like you were. And that, that made me be teary at the time. You know, it really affected me because I was like, well, I’ve got to do something about this. So I started Googling remote schools. And then this thing called Deadly Science was born.

And I started finding out that our schools are just really under resourced, like those school that I found with 15 books and it’s whole school.

[00:17:52] Melanie: Inredible

[00:17:53] Corey: and I have, you know, schools every single day or every week approaching me to be part of Deadly Science because of the lack of resources.

[00:18:01] Melanie: Everything I heard in a previous interview that you personally went into a bookstore and threw down a thousand dollars to get a whole bunch of books to send.

[00:18:11] Corey: It was not uncommon for me to do that. Not uncommon at all. I spent a lot of time, buying books and packing books and

[00:18:19] Melanie: what’s the book that you’ve bought and packed the most? Do you think, apart from your own.

[00:18:23] Corey: I’ve actually got a book next to me that I send.

I’m sorry, it’s got a receipt. This book here. As you can see

[00:18:28] Melanie: upside down?

[00:18:29] Corey: Yeah. This book is by, Sami, Sa mi Bayly and she’s, she writes all these really cool funky animal books. And I’ll say that she’s got three of these out at the moment and they’re just, they’re just got beautiful illustrations in them. And really cool party facts. I would say that like her books are probably up there with the ones that I would send out the most. Matt Chan, Thomas Mayer as well. All these authors they’re probably at the top. But like I I’ve moved on from like, I don’t just send books. I send telescopes, I send microscopes, I send solar kits, I send construction kits.

I send veggie patches. I send everything because our kids deserve to be able to find, you know, whatever, whatever they need and their passions. So, Yeah, we all had different flavors. We all have different needs and wants and, and passions. And, so that’s why Deadly Science works. We send stuff that, you know, mathematics stuff, we send chemistry, we send all of it because. It doesn’t matter what your flavor is or what you like is that you should have the opportunity to explore what your passion is. And that’s basically providing these children with the opportunity to find, to find their passion. And that’s the most important thing.

[00:19:39] Melanie: And if listeners were interested in supporting your work through Deadly Science, how can they do that?

[00:19:45] Corey: They can chuck us a donation, which is greatly appreciated so they can help us purchase more resources. They can volunteer their time at us. They can, share us on social media, like us follow, you know, because the more people that find out about the work that is being done, the closer we get to the person that may be out to support us properly in terms of, you know, providing us with, with large philanthropic donation or, or, you know, maybe they’ve got some kits themselves and they can send, them schools. So it’s just important that even if you can’t donate that any you dig what I’m saying and you love it, you just follow us as well, because you’re doing your bit as well. And this, you know, our greatest strength is our advocacy because, the images we generally see are people in lab coats, so your Thomas Edison’s and your Albert Einstein’s and I’m sorry, they’ve had their time in the sun. It’s time to as Australians, as the world, talk about , the world’s oldest living culture, 65,000 plus years of science and engineering and mathematics.

[00:20:45] Melanie: Yeah. Oh, look, we talk about decolonizing engineering at Engineers Without Borders. We have a ‘Pathways’ project, which the first stage started this year. And we’re basically. Documenting and researching, the need for the engineering sector, both businesses and individuals, non-indigenous people to change and then looking at what that actually requires.

So, how do we shape an engineering profession? That’s tangible, relevant and possible for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, you know, how do we have safe culturally inclusive workplaces? And you know, what, what would a decolonized engineering sector look like?

[00:21:22] Corey: Well, for one, it starts with no longer defining, you know, who wears a hard hat and, and why?

It’s, it’s about positive engagement. It’s about the right language. It’s the right, you know, we’re not doing this to feel good. We’re doing this because it’s the right thing to do. And, you know, sometimes the best journeys start with was that we don’t want to hear. And, and those was that we don’t want to hear generally, this isn’t really applicable to Aboriginal people because it’s built on a white system. Sometimes the best journeys are those walked together and, you know, we need to listen. And when you’re listen to our Aboriginal communities, our schools, what is it that we need to do to make it more, to make engineering safer for people of color, safer for women safer for, you know, our LGBTQ community, how do we make it safe?

And it’s not just putting, you know, well, it’s not just doing a Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) because sometimes when we do a RAP plan, we forget about the action sometimes the best actions done with your ears and then preparing for that. So I think that, you know, we have a lot to do as a society in terms of making things equal and fair.

In engineering we do in science, we do, I myself have to improve in areas that, you know, The best journeys of those walk together. And, and they are, you know, and that, and this is what we need to do as a society. We need to walk hand in hand with First Nations people and, and say, you know what, the past wasn’t okay, but let’s celebrate, the culture. Let’s celebrate the, the beautiful things that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people bring to this country. And it’s not. Sport and art, you know, let’s, let’s encourage kids. Let’s, let’s give kids recognition for things other than sport and art

[00:23:16] Melanie: absolutely. Last year we worked with a group from our sector to establish Engineers Declare, which is the sector’s response to the biodiversity and climate crisis. And it was absolutely key when we wrote out the declaration to ensure that, we were, acknowledging First Nations, as the original engineers. And just to go to what you said about, about the listening how do we listen and learn from Aboriginal peoples, you know, original engineering practices and their deep, deep and lasting knowledge? How do we weave that into our engineering practice?

[00:23:53] Corey: Yeah, for sure. And part of that is going on the journey, we have in Australia, you know, the world’s oldest fish traps, which are 40,000 years old, but the pyramids are only 4,000 years old. How can we celebrate the pyramids if we’re not going to celebrate the oldest structures in the world that are right here in Australia, we need to start acknowledging them.

And to do that, we need to acknowledge the terrible history that comes with that as well. But when you acknowledge the bad and you, you accept responsibility for the things you’ve done wrong, you also get to enjoy some of the things that we’ve done, right.

[00:24:25] Melanie: Absolutely.

Well in turning to your incredible book, which is called. ‘The First Scientist: deadly inventions and innovations from Australia’s First Peoples’, with beautiful illustrations by Blak Douglas. They really caught my eye and I’m sure every person who’s picked up the book would say the same. I’m just curious do you have, a favorite first in the book?

[00:24:50] Corey: I like all the books, but that would be unfair for me to say, because I wrote the thing, but

[00:24:55] Melanie: I think that would be fair.

[00:24:57] Corey: Now I wrote about a lot of my deadly scientists in the book towards the back of the book and, and I wanted to make it relevant. So not just talk about the past, like it’s not here, but also talk about the present science, the Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander people are doing in this book. But to see their faces, you know, when they get to see themselves in a book, you know, like for me, Like, imagine you imagine back to when you were a kid and you’re picking up a science book and you see Albert Einstein in there, but you don’t see David Ripon, you know, Australia’s greatest inventor.

He’s on a $50 note. Now, if you were to be a young kid and you were to see yourself in a book, imagine what that does for you as. To know that other kids around Australia potentially around the world are going to be reading about how you love science in your classroom. What are proud moment! And it’s like, you know, and the kids of color to see themselves as scientists is, is something. I hope that is life-changing because they deserve it. And anything, any accolades that come to me or Deadly Science along the way are completely irrelevant unless we make it our responsibility to make those awards accessible to them.

[00:26:06] Melanie: I’ve seen some beautiful images by social media of the children’s celebrating, receiving their first copies, you know, coated up in the white lab coat. Yeah. Just really celebrating the success of the book as success of themselves. It’s been really heart warming to see.

And imagine what that does to kids. Right. You talk to him and you put on a lab. Suddenly, you’re not, you’re not a child, you’re not in a school anymore. You’re a scientist. And without sounding egotistical, but without deadly science and without me working with that school, I doubt that that would have happened.

Yeah,

[00:26:43] Corey: that is a very special thing for me because. I think that that’s up there with teaching kids, how to rate in, in the greatest achievements of my life. I’m 29. And I have created something that, that kids in remote communities are finding their passions for. And they’re just absolutely loving it.

And, and you know what they’re doing at the same time they’re doing what I did when I was a kid. When people told me I couldn’t do things and they’re proving them wrong.

[00:27:12] Melanie: So important. Yeah. It’s very special. Absolutely.

I wouldn’t mind going to just a couple of questions around , before you wrote this book and you were conceptualizing, what kind of impact were you hoping to achieve? Why was it important that you write this book?

[00:27:30] Corey: I’ve sent over 20,000 resources off to remote schools now, I’ve spent majority of my time every week in post offices, sending books. I wanted to create something that was going to be a gift to the next generation in the sense that non-indigenous kids learning about Aboriginal people in a way that they have never learned about Aboriginal people before, in the hope that they would respect our people more . That’s the hope. But on the other side of the coin, I wanted Aboriginal kids to grow up in Australia, feeling strong, deadly, passionate, because they could see themselves as scientists and, and coming from the world’s first scientists. And, I didn’t care if one copy sold or a million or whatever, it didn’t matter. As long as it was a book I could send out to those kids that would help change it for them. And the idea in my head was to, to make it accessible. And not worry about the politics. Work with who, you know, and work with people that will help you write this book and do it well and do it in a respectful way.

And let’s, let’s change the future. Let’s, let’s give these kids a bit of inspo to, to try to strive and achieve and, and, and a book they’ll enjoy. When I came up with the idea. I probably had eight or nine books that I could have written. There was so much, I wrote, so many people I spoke to, but I want this book to be not about me as an author, but to be the thing that people look back in 10 to 20 years time and say, you know what? That book led to a whole new conversation, which led Australia to becoming a better place.

[00:29:09] Melanie: Wow. Oh, audacious goals.

[00:29:11] Corey: But you know, and I think that that’s, that’s why it’s written in the way.

[00:29:15] Melanie: Yeah, which is remarkable. And also to see a book that’s targeted to that age group, that’s seven to 12 where, you know, their ideas of self are really forming. They’re starting to forecast, you know, who and what they want to be in the world.

Actually, that, that is one question I was hoping that we can squeeze in, in terms of engaging with, the people, the communities, the schools, the children who helped, formulate this book. What was that process like? How did you go about that?

[00:29:46] Corey: Yeah, it was quite challenging at times. There was a lot of conversations. There was a lot of hard conversations. There’s a lot of emailing back and forward. There’s a lot of excitement. I knew I had to write about the Robinson river kids. And I knew I had to write about the many Alec kids I knew I had to write about, you know, the Grid Island kids that we work with. I wish I could have put them all in the book to be honest, but I. Well, I knew I had to put them in there because what they were doing, you know, and again, I’m not get all the accolades for what these kids are doing, they’re changing the future for their people and they, and they’re doing it and they’re doing it with a smile on their face face, and they’re doing it without, you know, with the, like, with the most joy. And, and I think that, it’s just really important for, for young people to, to realize that they are, you know, they’re making these changes and it’s a big deal. Like it’s a really big deal. So we at Deadly Science. We celebrate them any time, any chance we get. And, and again, the other thing as well is that when you, when you flick on your news and you flick on your newspaper or whatever, but yeah, majority, the images you see of Aboriginal kids is negative.

So. Who’s telling the good stories, because to be negative, to have negative stories, you must have good stories. And, I think that’s something that Deadly Science does really well is that we tell the stories of the kids that are loving remote learning. They’re loving school. They’re, they’re loving science and you’re are, will defend them to the teeth because they deserve to have a future where they’re not persecuted due to their race.

[00:31:17] Melanie: Well, Corey, we’re just about at time. I just use the last couple of minutes, for the guests to do a shout out, for anything that they’re passionate in, our podcast is called ‘The Actioneers,’, love to hear things that you’re taking action on, be it, your book and your charity or otherwise. But yeah, it’s just a shout out moment for you to soapbox.

[00:31:38] Corey: Yeah, Chuck us the follow on Deadly Science or whatever your social media platform is, but also, check out the women in stem movement, check out Indigenous Literacy Foundation, check out your, your local Aboriginal community and see what they’re getting up to, and, and shout out to all the mob out their, that may be.listening.

[00:31:55] Melanie: Amazing. Corey, thank you so much for sharing your story, for being vulnerable with us. For taking us on a journey, which was, eventful, it was wild. It was deadly. And congratulations so much on the success of your book. The First Scientists.

[00:32:11] Corey: Thank you so much for having me. It’s an absolute pleasure.

Thanks Corey,