Patrick carries around five second-hand phones. On the weekends, he straps them onto the dashboard of his car and takes them for a drive through Sydney’s streets. Patrick’s not a covert criminal running some kind of dodgy operation. He’s conducting important work on a project that will create incredible freedoms for people in Cambodia living with disability.

Patrick Joy is our lead volunteer on the development of a dashboard quite different from the one in your car. It’s one that will track and assess critical data that will feed into the design of a vehicle which will create independent transport for people in Cambodia who are wheelchair-bound. It’s a life-changing proposition for these individuals, enabling them to be independent, earn a living, contribute to their communities, and have the freedoms to live a life they aspire to.

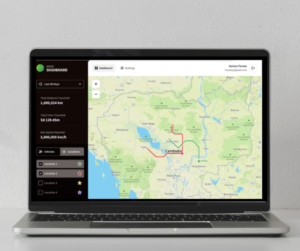

Patrick volunteers as part of the Accessible Moto Software Dashboard team, one of EWB’s mobilisation projects. He’s building on the work done by a team from the University of WA, who at the end of 2020 had completed research and development of the first iteration of an app. It’s an app that will be installed on phones which will be secured to five Accessible Moto prototypes in rural Cambodia (see feature photo). The data from these phones will feed into a baseline study to enable our Technology Development team to understand how the motos are used to inform further development of the vehicle. Patrick has been working to further refine the app and conduct initial field testing on different platforms – a critical phase to assess any potential failings or technical challenges of the device. And there have been a few.

Phone hacking for good

The team has trialled a range of different devices to capture and deliver the data – and a phone has been determined as the best fit, possessing the right balance of capability and cost. With all the hardware needed to enable data tracking, a reliable cellular connection that can transfer data, and a robust casing for when the unit is subject to rough terrain, it’s a walk-up unit with a lot of advantages. But it also came with a number of downsides.

Firstly, it needed to be hackable. Root access to the base operating system and hardware was needed in order to change the way the phone operates. Typically mobile phones require a user to press a power button to turn the device on, and need a pin or pattern code to initiate applications and data connections. As this device would be locked in a box, it needed to have the capacity to automatically switch on, when the moto was on the move. This has been one of the biggest hurdles and was almost a project-stopper.

This problem was solved by modifying the device’s boot software to detect when power is supplied to the phone and subsequently switch the phone on. The android operating system was then hacked to bypass the standard startup process, initiate the device data and location services and start the EWB application. When the moto stops moving, the phone is powered down, to avoid completely draining the battery during periods of inactivity.

Secondly, it had to be cost-effective. Whilst some of the more state-of-the-art phones may have been easier to manipulate to the needs of this project, the slim budget for the project made this option prohibitive. Higher costs also put the longer-term sustainability of the project and the ability to collect data for longitudinal study, at risk. As a component in the total moto package, it needs to be low-cost. People with disability in Cambodia fall within the lowest 20% of income earners, so the affordability of the final product is vital.

Accessible moto dashboards under development for internal trialling

Finding a phone that was hackable, available and cost-effective was quite a challenge. Every phone manufacturer uses different underlying hardware and software, so every phone candidate had to be physically tested to determine suitability. We put out a call to the wider EWB community for device donations and we received a great response. Some devices survived the testing, while others were “bricked”, a term used to describe the usefulness of a device when hacking attempts fail. The team settled on refurbished Google Pixel 2 phones that cost around $170 a pop.

With the best device determined, the team then created a system architecture and developed the backend software (using Amazon AWS) that can accept the data coming in from each of the phones. This is fed into a database, from which the data visualisation expert in the team – Kristina Mahoney – can then analyse and present the findings.

Volunteering technical skills

For Patrick, this is his first volunteer project with EWB and indeed, his first experience of volunteering. Having seen a call-out on LinkedIn for software engineers to work on this project, Patrick was attracted to the opportunity to apply his technical skills to a worthy initiative.

Patrick grew up in rural Ireland, and was always intrigued by computers and programming. As a kid, he’d go down the road to a neighbour’s house to access one of the only computers in the village (an IBM 086). He studied electrical engineering, but never really practiced what he’d learned. Instead, he moved straight into asset management, working on maintaining heavy assets in the oil, gas and transport sectors.

Moving to Australia in 2003, he’s worked with BHP, Pacific National Rail and NSW Transport, ahead of starting his own consultancy, Think Transit, with the aim of bringing technical and cutting-edge methodologies into transport and related industries.

“This project is a great avenue for people, like myself, to use their skills in a tangible way to support people less fortunate. My understanding of volunteering was that you either gave money or physically had to go to the country to contribute. With a busy life it is not that easy to find the time to volunteer – it’s been great to be able to do it from my living room,” said Patrick.

One of the key highlights for Patrick has been how much he has learnt.

“Working with the rest of the team and meeting everyone, only online at this stage, has been great. But it has made me feel a bit old! Getting insights from the younger members into new technologies and methodologies in this space has been a highlight – I have learnt a lot from them.”

He’s also experienced some of the challenges of volunteering on a group project. Most people on the project, aside from the EWB staff guiding it, are contributing in a volunteer capacity. The differing availability of team members makes it hard to get everyone together. And you are often waiting on people to complete tasks upon which your work has dependencies.

The other challenge for Patrick was working on a project that demanded low-cost solutions. Not only does the project have a slim budget, but cost considerations need to be considered to ensure the long-term viability, and sustainability, of the solution. Affordability is key when the end-user is a low-income earner.

It takes a team to deliver

The Software Dashboard has been working on this project for almost a year, and comprise students, recent graduates, consultants and company founders, mostly from Sydney:

- Patrick Joy, who implements cutting edge technological solutions for the clients of his company Think Transit

- Nathan Lecompte, a student (and EWB chapter president) at Macquarie University and part-time front-end software engineer

- Kristina Mahony, from technology consultancy Accenture

- Nathan Lam, from a STEM social enterprise Code Create; and

- Matthew Imhoff, at the Australian Centre for Field Robotics at the University of Sydney (and all-round EWB volunteering legend).

What’s next?

With the phone tracking devices now taken through their paces, Sreimom – our original moto user and co-designer based in Cambodia – will have a device installed in a new, improved version of the accessible moto, to pilot and test the vehicle, as well as this new monitoring device. Three more motos are also being built, and will have phones installed, as part of this piloting phase. This is however all contingent on the impact COVID-19 is having in Cambodia – at the time of writing, many parts of Cambodia are in lockdown.

You can support this project

This Accessible Moto project has been developed in collaboration with Light For The World. Our work in Cambodia receives support from the Australian government’s NGO Cooperation Program (ANCP).

We also welcome partners to support this project, please contact our Partnerships team. You can also donate to our overseas work, or sign up to learn of future volunteering opportunities.