Despite significant progress over the years to increase access to rural sanitation services, Cambodia continues to report the highest rate of open defecation in the region. In 2011, to address the many health and environmental issues associated with open defecation, the government of Cambodia announced an ambitious target to reach 100 percent coverage of rural sanitation services by 2025.

In most cases, pour-flush toilets are the recommended sanitation technology to help meet Cambodia’s target. However, Cambodia’s challenging geography in rural areas makes conventional toilets difficult to construct for a number of reasons and increases the likelihood of environmental contamination.

As part of EWB Australia’s Sanitation in Challenging Environment program, EWB is working with two communities in Kampong Chhnang province to provide sanitation solutions that are appropriate for the hard ground environment characteristics present in the region. In partnership with EWB’s community partners, RainWater Cambodia and the Provincial Department of Rural Development (PDRD), EWB has recently piloted two new sanitation solutions in Trapeang Anhchanh village and Ou Totueng village, benefiting 15 households and 71 community members.

Challenges of a ‘hard ground’ environment

There are a number of challenges associated with sanitation in hard ground environments, both within Cambodia and globally:

Access to groundwater

The groundwater table varies in depth across Cambodia, however, regardless of depth, accessing this resource can prove challenging in hard ground environments. This is particularly relevant in rural communities where access to machinery is limited, making stiff clay and rocky soils difficult to excavate and hence more difficult to excavate down to the groundwater table to install extraction wells.

Low infiltration rate

Average infiltration rates (the process by which water on the ground surface enters the soil) are low in Cambodia. Consequently, groundwater recharge (where water moves from the surface) and transmissivity rates (the rate of flow) are also low. In hard ground environments, groundwater recharge rates and aquifer properties have the potential to be limiting factors when it comes to developing feasible sanitation solutions.

Groundwater contamination

Groundwater can be difficult to access due to the challenges associated with excavation in hard ground environments. In addition to this, there is the risk that hard subsurface rock can be fractured during excavation, potentially exposing the groundwater table to harmful contaminants present on the ground surface. This is problematic for technologies such as underground septic systems whereby rock fractured during the process to excavate has the potential to expose the groundwater and surrounding soils to pathogens and contaminants if a leak were to occur from the septic tank. The risk is similar for underground pipes.

Difficulty excavating soils

Hard ground environments are difficult to excavate. Without sufficient excavation equipment, infrastructure cannot be placed far enough below ground level to prevent damage from activity above ground. As was observed in water supply projects previously completed by EWB Australia in Koh Tnout and Ksach Leav, water distribution pipes were damaged due to motorbikes and livestock walking over pipes that could not be buried far enough underground due to the presence of stiff clay and gravel.

Seasonal variability in soil properties

Like most South-East Asian nations, Cambodia has a distinct wet season and dry season. This seasonal variability can impact soil and groundwater properties during each season. Soil strength is generally harder in the dry season and softer in the wet season. This impacts the structural design aspects of developing a sanitation technology, in that the ‘worst-case’ soil properties must be used in the design calculations to ensure the infrastructure is structurally sound throughout the year.

Kampong Chhnang province

Kampong Chhnang is one of the central provinces of Cambodia. Trapang Anhchanh village of Kraing Dey Meas commune, and Ou Totueng village of Svay Chrum commune, Rolea B’ier district were selected as the target areas for this program based on the recommendation of EWB’s partner PDRD.

Trapang Anhchanh village is home to 1065 people, 331 families and 310 households. Local data classifies 45 households in the village as ‘very poor’ and 71 households as ‘poor’. Ou Totueng village is home to 376 people, 94 families and 85 households. In Ou Totueng village, 4 households were classified as ‘very poor’ and 20 households classified as ‘poor’. The majority of households in these two villages rely on farming (rice crops and plantation) for their livelihoods.

In preparation for this program, EWB collected baseline data during two site visits to Trapang Anhchanh and Ou Totueng in November 2021. With support from EWB’s partner PDRD, 14 households were interviewed to collect information about their access to sanitation. Village chiefs also supported wider community engagement to gather information from the community about the challenges associated with accessing sanitation in hard ground environments.

Example of a household pit latrine used by households in Trapang Anhchanh village. The latrine has a broken ring, resulting in faecal sludge leaking to the surrounding soil.

Baseline data collected from site visits in Trapang Anhchanh village found that some household toilets were being shared by up to 7 households (or more than 30 people) because not all households could afford their own toilet. This resulted in issues such as clogging, waste overflow and an unpleasant odour. Baseline data also found that shared toilets were not accessible for all households as some shared toilets were difficult to use and dangerous to access for people living with a physical disability.

In Ou Totueng village, it was found that 65% of households had access to their own toilet. Baseline data found that existing toilets in the village were malfunctioning. Issues included clogging, an unpleasant odour, waste overflow, latrine pits requiring frequent emptying and broken or cracked latrine pits, resulting in environmental contamination. The impermeability of hard clay soil, run-off water penetrating into the pit and the age of the toilets is reported to have caused these malfunctions. Baseline data revealed that unsafe faecal sludge management was also being practised to manage the issue of latrine pits becoming full quickly, increasing the risk to community health and environmental pollution.

The time and cost challenges associated with the hard ground environment present in the region meant that building a conventional latrine system was not an option for many households living in Trapang Anhchanh and Ou Totueng.

Solution #1: Twin pit latrine

Technology Development Specialist Mariny Chheang and EWB Australia in Cambodia volunteer Kit Kann designing a prototype of the twin pit latrine system.

In response to the challenging environment present in Kampong Chhnang province, the EWB Australia team in Cambodia designed a twin pit latrine system utilising concrete rings. Conventional concrete ring latrines are typically built with three concrete rings assembled vertically, requiring an excavation depth of 1.5m. As a result, conventional concrete ring latrine systems can be challenging and costly to construct in a hard ground environment.

The advantage of utilising only two concrete rings in the twin pit latrine system as opposed to three is that less depth is required for installation, therefore reducing the risk of hitting the groundwater table and contaminating local groundwater. The twin pit latrine system is also designed to withstand flooding, as the latrine slab is installed 20-30 cm above the localised flood level to reduce the potential for water contamination.

How does it work?

Prototype sketches of the twin pit latrine system.

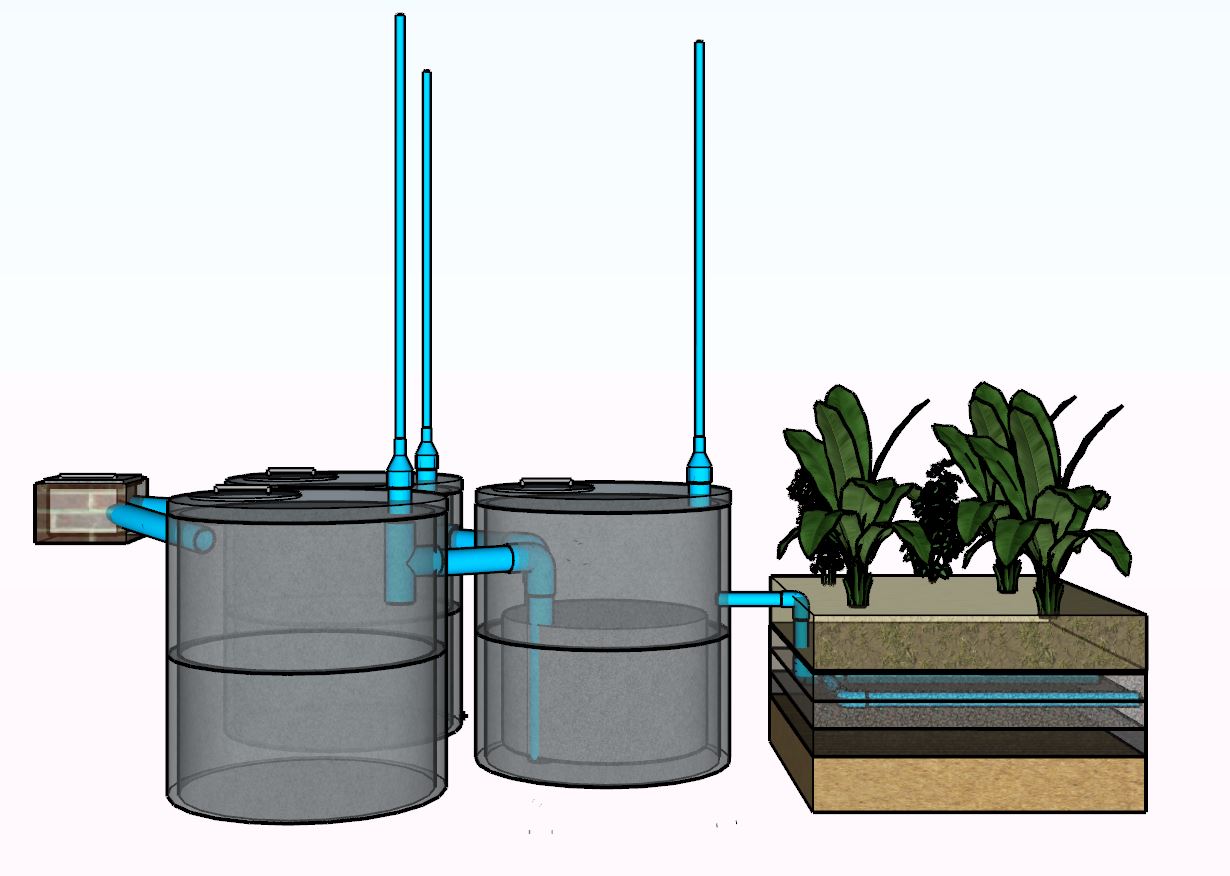

The main components of the twin pit latrine system include a toilet pan, switching box, twin pit, soak pit and a leach field. The latrine system collects waste from the toilet pan, which flows into a rectangular-shaped switching box. The waste is separated by density; solid faecal waste will flow into one pit of the twin pit system, while liquid waste flows from the twin pit directly into the soak pit. The soak pit contains construction aggregate, which serves as the secondary chamber to treat the wastewater before it flows into the leach field. The leach field, which contains aggregate, charcoal and sand, removes pathogens from the wastewater before the wastewater gradually filters out into the surrounding environment.

Once the first pit is full of faecal sludge and can no longer accept waste, the switching box diverts waste collected from the toilet pan into the second empty pit. The contents of the first full pit will decompose over time and transform into humus. It is estimated that each pit will take two years to become full, depending on frequency of use. By the time the second pit becomes full, the contents of the first pit will have decomposed into humus and can be emptied by a faecal sludge management service. The emptied pit is then reconnected to the latrine, ready for use. This cycle is repeated, ensuring uninterrupted use of the latrine system year-round.

To ensure the latrine system can withstand the challenges brought on by Cambodia’s wet and dry seasons, a control valve was installed to control the flow of water between the soak pit and the leach field. During the wet season, the control valve must be closed to prevent runoff water entering the pit system through the pipe. During the dry season, the control valve stays open to allow the liquid waste to flow from the soak pit into the leach field.

What are the advantages?

- On-site faecal sludge management

- Uninterrupted use of the latrine system year-round

- Utilises locally sourced and cost effective materials such as concrete

- Requires a small excavation depth (0.7m) in comparison to conventional latrine designs (1.5m)

Following extensive prototyping, ten twin pit latrine systems were installed across Trapeang Anhchanh village and Ou Totueng village.

Construction of the two concrete ring latrine system.

Solution #2: Septic tank

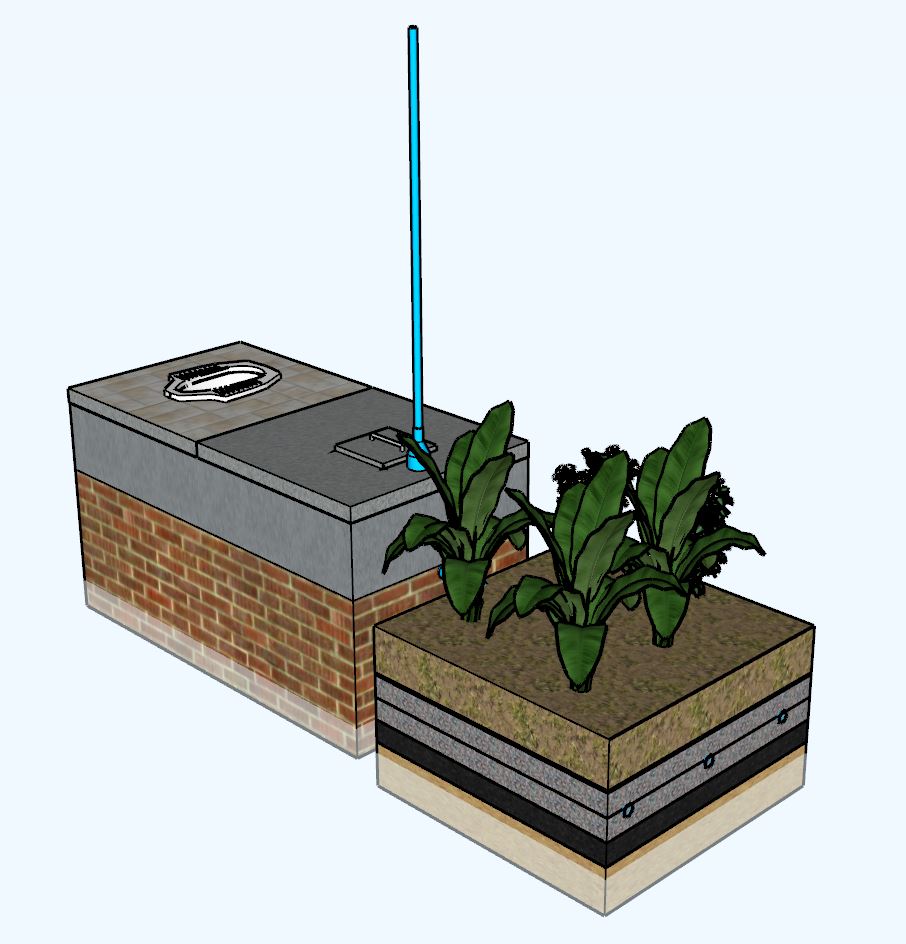

As opposed to the twin pit latrine system, the septic tank design requires less space, as the toilet pan is built into the septic tank. This is being explored as an alternative option, as during initial community consultation, the team identified that many households in Trapeang Anhchanh village had limited available space for the construction of a latrine system.

The septic tank system is designed for households with limited space, measuring a total of 1m (width) x 2m (length) x 1m (height). Similar to the twin pit latrine system, the septic tank requires an excavation depth of 0.7m.

Prototype sketches of the septic tank design.

How does it work?

The septic tank consists of two chambers; the upper chamber functions as a scum barrier that prevents scum from clogging the outlet pipe, whilst the lower chamber functions as a sludge barrier. The two chamber system ensures only liquid waste can flow into the leach field through the outlet pipe. Similar to the twin pit latrine system, the leach field contains gravel, charcoal and sand. Wastewater passes through the leach field, which removes the majority of pathogens and reduces the risk of environmental contamination on local groundwater.

A two metre vent pipe located on top of the septic tank ventilates the air inside the two chambers, releasing odours above. The vent pipe can be removed if the outlet pipe becomes clogged and needs to be investigated.

Once the septic tank is ready to be emptied, faecal sludge is accessed via the cover on top of the tank. Beneficiaries were guided through the process to operate and maintain the septic tank following the construction of the latrine system.

What are the advantages?

- Efficient use of available space

- Utilises locally sourced and cost effective materials such as bricks

- Requires a small excavation depth (0.7m) in comparison to conventional latrine designs (1.5m)

Five septic tank systems were installed across Trapeang Anhchanh village and Ou Totueng village.

Next steps

Program Support Officer Chanrika Keo and construction Project Manager Yin Sopea on-site in Kampong Chheang province.

This project was piloted in June 2022 across two villages in Kampong Chhnang. Our team will continue to monitor the success of the two latrine systems through three site visits over the next 12 months, with monthly remote monitoring to track the efficiency of the system. The technology will then be refined in preparation for scale up across Cambodia.

This project received support from the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through the Australian NGO Cooperation Program.

If you would like to support EWB’s work with communities overseas, please donate here.